The Ouroboros Mirror

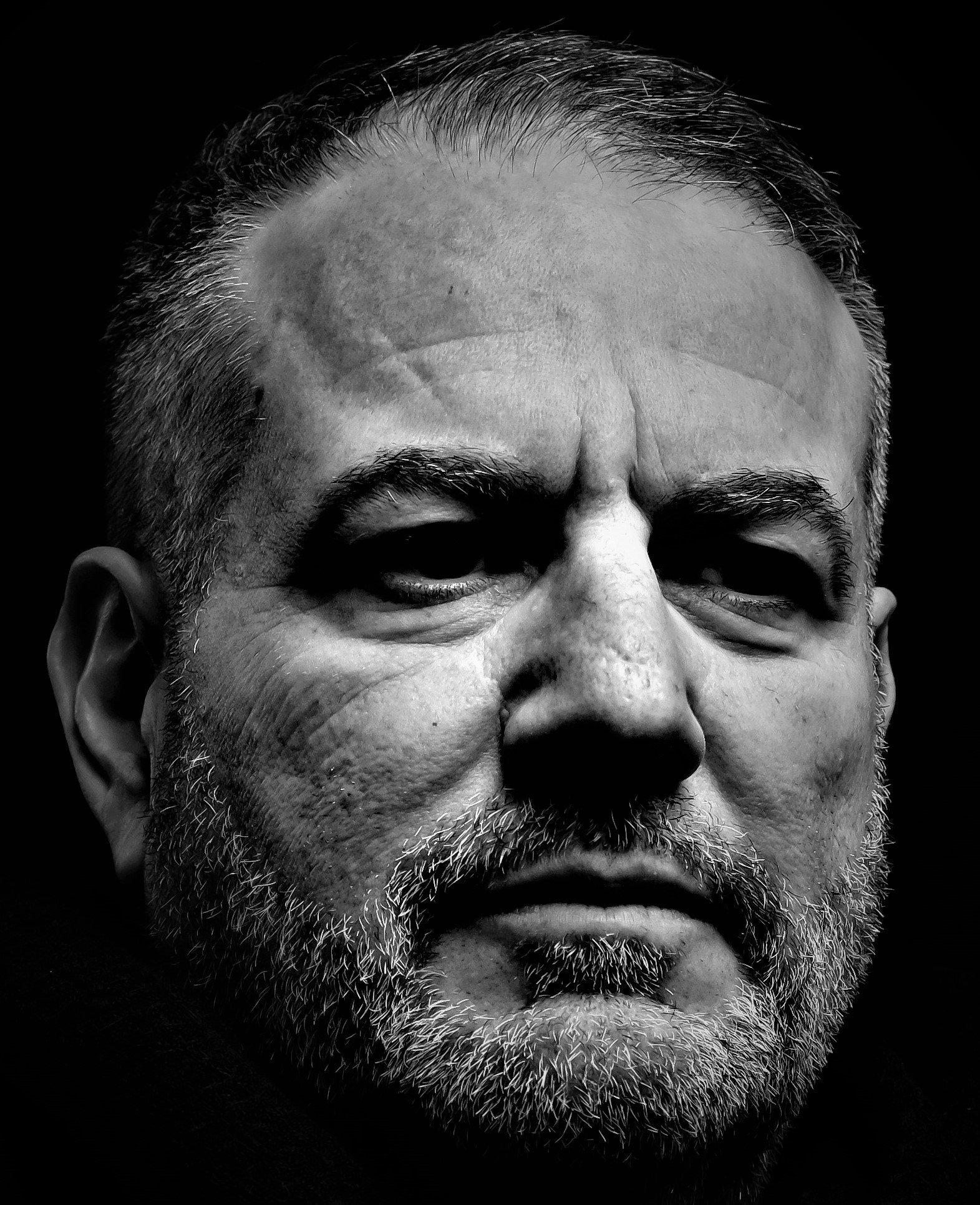

—Basil Rosa—

In the 1980s, while wearing red leather pants, it hit me—I was a girl in a man’s body. Bopping about, my hair spiked and dyed peacock blue, a ring in one nostril, I wanted to be Cindy Lauper. I kept my Sony Walkman and earbuds on, determined never to conform or lose the humor and optimism my favorites songs delivered, though I vacillated between “Cruel Summer” by Bananarama, and Funboy Three’s “The Lunatics Are Taking Over The Asylum.”

To all who’ve taught me love, etched into the unknowable that parents us, for you naked one hour per day, I stand here like Prufrock scared of a peach, eyes closed, in front of what I call the Ouroboros Mirror and become a dragon eating its tail. No oracles, no doom-scrolling allowed while my fingers walk the flesh of my torso.

Needs loom. Wants fade. I make no claims on infinity. That which once consumed now gives. I lived for too long following the dictates of Zugunruhe, a German word to describe an instinctive migratory restlessness in birds. Now, blinds drawn, appliances unplugged, the air hardens my nipples. I still remember older boys I had crushes on who died of AIDS. Goals remain in thrall to light and fate. I consume myself discretely, awakened to polarities. What is the soul? The secular me, once so bold, used to know. Not any longer. I’m two in one, always have been, so what? It means nothing without reverence for the sacred. I’m not talking religion. I mean that what I’ve come to is a belief that a baffled silence confirms my wariness toward all human constructs of identity. I don’t have any truth. Neither do you. I follow scenes as they unfold. Either avoid or embrace them. To be is to reach. To wait. We’re one blended spirit in perpetual emergence. Yet we amuse ourselves with symbols, order, groupthink, unwilling to see our lies and delusions.

********************

This would be the day I’d come out. Viewed by our peers as her boyfriend, I was with Consuela Fittipald riding our bicycles at Colt State Park where families gathered around picnic tables for a barbecue, children kicked balls, tossed Frisbees, flew kites, and young mothers pushed baby strollers. I wanted to scream at the clear sky as breezes fused barbecued meat aromas with a pleasing mix of honeysuckle and brine.

Consuela—never Connie—and I skittered along a dirt trail through freckled sunlight. We veered into sleepy expanses of fescue that fringed scrub pines where, from picnic tables, one could view Mount Hope Bay. Sailboats passed through beams that dappled the bay’s currents. Deep into the park, away from boisterous activity, we reached a glade and an outdoor chapel where we set our bikes down. We pushed away acorns to lie side by side on our backs on a moss-flecked stone altar. There, staring up at trees, I understood that Consuela—ever sultry and restrained—wanted to kiss me. We lay so close, face to face, our noses almost touching. But I didn’t want her. I wanted to be her.

“You ever think, Consuela, and be honest, that you’re not who you’re supposed to be?”

“My God, that’s all I think.”

There abided a calm between us. The air smelled of pine sap. Squirrels sprinted up trees. I released a long sigh and fell from sweet lassitude into despair. “I’m not who I am. Or I am who I’m not.”

With a smile, pushing back tresses of black hair, she said, “You’re my mystery man.”

Mystery woman. I didn’t say it. I hungered to. Everything hurt. Life was so serious. Breezes nudged tree limbs and I heard them creaking. If only to sob or shout, but Consuela kept talking about how the more she pushed herself, the better she felt. This was girl talk. What I craved. She said there was a lesson in each day. She needed to conquer fears. Fulfill desires.

I told her I loved the exhaustion I felt after our rides, that I trusted what it did for my body. I liked breathing as if my energy would never wane. I planned to live forever.

********************

Due to many an afternoon with Consuela, I began to emerge, learning to talk and move like her. Keeping it a secret from my mother, my only parent, I wore the kinds of clothes she bought, including her panties. I can be this person I am. It terrified me. Who could I trust? Only Consuela, but in furtive discrete doses. She had expensive taste, so I did too. After my classes and part-time job, I studied until dawn determined to excel. My mother never expected I’d go to college. I earned a scholarship. One day, I’d prove the doubters wrong. In heels and lipstick in a graduation gown I’d raise my diploma and shriek, “Look at me, Lucas, I did it!”

I began writing poems. I wanted nothing from them. They were about youth, desire, Consuela, food, sex, the father I hadn’t known, art, anger, love, Andy Warhol, all the pricks out there, and the sea. Lots of undisciplined-villanelles about waves, sea glass, and periwinkles. Behaving as a reserved, buttoned-down scholar, old before my time, all I lacked was a cardigan and loafers. I rented a third-floor apartment under a sloped ceiling. A desk, small bed, meager rent. Old Rosalyn, my landlady who lived below me, loved to cook. We ate together now and then. I helped with her English. She with my Spanish. All her recipes were in her head and I’d write them down as she shared them. In winter, her oven warmed my creaky floor with heavenly fumes. I kept telling myself: just let yourself burn. I thought myself naïve. I hadn’t yet learned that being is not allowed. People asked what did I do. Well, I refused to join clubs, go to parties, or offer details about the chaos inside my head. I seriously considered learning Greek. The sea, preparing food, masturbation, and cycling suited me well.

Long after student days, living in a Park Slope coop when Brooklyn was still cheap, I had men. Lots of them. I read Capote, Paul Monette, Djuna Barnes. Not love, mind you. Sex. I made visits to the West Village. I learned codes, the meta-language, how to signal and be seen, how to dress, where and how to walk the night city. I went to my job, lunching each day at Bryant park and watching trees. I starved myself thin as I listened to how I breathed. I didn’t know who I was. Neither did my men. Release was all. I never saw any of them a second time.

Now, I pinch my nipples as I draw in a breath. I’m still lean, beautiful, but worn smooth by erosions. As Rosalyn used to say: “If we don’t love ourselves, who will?”

********************

I heard her toilet flush and looked up to see Consuela in front of me, hands on her hips. The black negligee slipped from her shoulders and she was completely naked. She flinched seeing I didn’t want to gawk. I couldn’t.

“No.”

“No, what?”

That convergence point, all those black pubes, the nipples, the small soft belly. Like Blake’s sick rose, found out. As her face reddened, her scent filled the room.

I protruded my lower lip, trying to look respectful. “Please, let’s don’t spoil it.”

She began to approach, gently eager. “Spoil what, Lucas?”

I stared, not seeing a thing, smoldering with anger. I looked away. I just couldn’t be with her like that. So exposed, so hungry. I didn’t feel it. Then she, reading me, sounded a whimper and a snort of disgust before hurrying out. I heard her behind the closed door of the bathroom down the hall. She’d burst into flaming tears.

Once home, I tried to write a poem. Nothing. I stared at my bicycle tilted against one wall. I scanned the spines of books piled around me. I opened one, a collection of Robert Mapplethorpe images. I studied his use of light, or the paucity of it. The lack of cheerfulness in his faces. That was when I knew I’d go away. College, then Manhattan. Then I’d travel and never return. The pursuit of art would become my raison d’etre. I’d bring baggage. Nor would I ever forget Consuela. She had courage, showing me what I really wanted were my own instincts.

Longfellow comes to mind:

A boy’s will is the wind’s will,

And the thoughts of youth are long…

********************

I was on a train in Europe, living out of a suitcase, when I learned that Consuela had died of ovarian cancer. I began to weep. I started a letter to her husband, a man I’d never met and father of the two children Consuela had wanted. Upon completing it, I realized I didn’t have a postal address. I had her email, social media links, had promised to keep in touch, but never did.

I tore up the letter.

After days of too much self-pitying brandy, I wrote a bevy of short poems about her, then burned each one. I’d never rid myself of the guilt I felt.

Years became decades. As with any aging queen, my body flagged. Sex still happened, but it usually led me to feeling disappointed in myself.

Now I press the softer spaces between my ribs. Consuela died a long time ago, didn’t she? I didn’t kill her. She never died. She moved on. She’d found love. Her resilience proved time can be more blessing than curse.

I’m grayer now, my eyelids hooded, neither insouciant nor in a hurry. I value my evolving understandings of companionship. To live means to explore. The root of this word is commonly accepted as plorare from the Latin meaning to cry. Paired with the ex prefix, most etymologists define it in the context of hunting. Hunters had to shout when in new territory to attract locals and learn from them. Just as I’d once shouted with lustful eyes and a hard-on when cruising for sex during wilder days in the Village. The lesser discussed root, from the French pluere, means to make or flow. I prefer this etymology when thinking of Consuela. She understood early that nothing is static. I didn’t. For many years, aimlessly so, sometimes with purpose, I floated about learning how to sharpen my skills, accepting new ways to define ambitions, grafting myself on to landscapes and sinking in.

Migratory, I left crumbs behind. Few days passed without memories of my mother, of afternoon light gracing a Brooklyn brownstone in autumn, bike rides along the Hudson, bike rides with Consuela. There was never enough time to say a proper goodbye.

I’m still assembling myself. Naked, fading, I river along. I don’t ask what happens next.

********************

By the time I reached my early forties, I’d completed the first stage of a reinvention that would endure into my sixties. Having earned a second diploma, I moved to Los Angeles. I became a teacher. I met Arthur. Sex with him defined a way to reinvigorate passions I’d abandoned. Though we lived well in tony West Hollywood, Arthur, raised in Oregon, projected himself as a hippie miscreant, drinking away afternoons in bungholes such as the Smog Cutter and Jumbo’s Clown Room. I met him at a party and he’d said, “Any need, just call.” So, I did.

Ten years his junior and under his influence, I exchanged Wordsworth and Coleridge for Frank O’Hara and Baudelaire. I identified, if asked, as a Gen-Xer. I still despised categorization and being thought of as caring, female, eco-friendly or liberal-minded, though some of those determiners were required for matriculation in certain L.A. circles. Arthur used to introduce me as his “Republican cunt whore.” I rather liked that.

He liked that I wrote poetry more than I think he liked the poems. He derided me constantly, objecting to my concerns with tradition and how others viewed me, but he read my work closely and insisted that I was improving. I read Michael McClure upon his recommendation. Charles Bukowski, too, who left me cold, but who Arthur adored.

I was in my fifties before I started to claim any semblance of an aesthetic. Arthur helped with this, as well. He stipulated that I should always incorporate duende, and remember what mattered in art was whether resonance was felt after the experience. In general, poems and art felt sensual and continued to provide orgasmic highs. My standards changed and evolved. So did Arthur’s. Yet students got younger each year. Arthur’s contempt for them hardened. He saw his cultural references grow feebler as he attempted to sound relevant. As a form of encouragement, I copied a line from Lucille Clifton and taped it to the wall above his desk: These hips are free hips, they don’t like to be held back.

It didn’t help. Poor dear Arthur, miserable enough to consider suicide and infidelity, decided that since he was fluent in Chinese, he’d find work in Beijing. My Spanish wasn’t half bad. I suggested Buenos Aires, where I imagined learning to tango. It was at this time, watching with fear and disgust Arthur’s increasing dissolution, that I began this practice, in solitude, of using the Ouroboros Mirror.

The year was 2006 when the death of my mother fused me anew to what lay ahead. Hart Crane still resonated while the likes of Rimbaud felt adolescent. I was still with Arthur, though not in Buenos Aires or Beijing, but Shenzhen. While on the dreary flight back from her funeral, I experienced the epiphany that I craved the unfamiliar because it made me aware of a way of living I’d never achieved. I’d only thought I had. This was because I knew nothing about death.

Shenzhen wouldn’t teach me. Though the city was booming and hadn’t yet swelled with new arrivals from the West, I still found it dull. Sex no longer enflamed or felt profound, but to paraphrase Oscar Wilde: Arthur and I were arguing against the provision that life is too tragic to take seriously.

Without pensions, investments, or much in savings, we still had good teeth and jobs. Arthur’s, paid in dollars by an American university, included health insurance. Mine in RMB at a locally-run private school. It wasn’t enough. Worried that a horrible change was coming, I began, as many Chinese do, to obsessively squirrel away my earnings. My lack of Mandarin, difficult to learn, was a liability, though Macau and Hong Kong were easy visits I enjoyed. Arthur didn’t like the way I leaned on him. He scolded me. “Learn it, Lucas. Knowing the lingua franca changes everything.”

His unhappiness evaporated when he reconnected with Fen Li, a friend from university days. Arthur found in Fen Li the rejuvenation he wanted. Fen Li had resided in Silver Lake, where he and Arthur had met, before leaving to teach economics at a Hong Kong university. Knowing I’d soon be out, I broke up with Arthur. What angered him was that I remained civil. He would have preferred me to be nasty, mealy-mouthed, but I was too weary for theatrics.

One day, having purchased a plane ticket to start fresh in San Francisco, I ventured out alone, shoved along on the tide that defined much Shenzhen street life. Enduring the humidity and physical contact, I journeyed by bus to the Luohu district and the first Walmart built on mainland China. It was massive and, most importantly, air-conditioned. As I rode the escalator, a Pipa melody played from the ceiling. I stared at other Chinese to confirm they were not in costume and I was actually where I thought I was. I saw a group of newly arrived hopefuls, so skinny, dressed in village rags. They’d come from the countryside eager to work fifteen-hour factory shifts for a dollar a day. Road dirt streaked into their faces, hope and desire were their claims in this opulently modern sphere, so new to them.

I watched as they gawked in infantile astonishment at the awesome size of flat-panel TV screens. A dozen covered a wall, each flickering and drawing the gawkers in. I gawked too. They took my mind off Arthur and trepidations about my future and how I didn’t hate Fen Li, couldn’t hate anyone, and would probably die alone.

Each image on those screens presented a life and comforts neither I nor those new arrivals would ever know. Sad, I suppose, but many a dragon eats its tail, and my hips, like theirs, wouldn’t be held back.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Basil Rosa’s stories have appeared in Argyle, Skipjack, and Blood + Honey. Novels include Witness Marks, and A Million Miles From Tehran. You can find him online at https://jmfbr1.blogspot.com/.